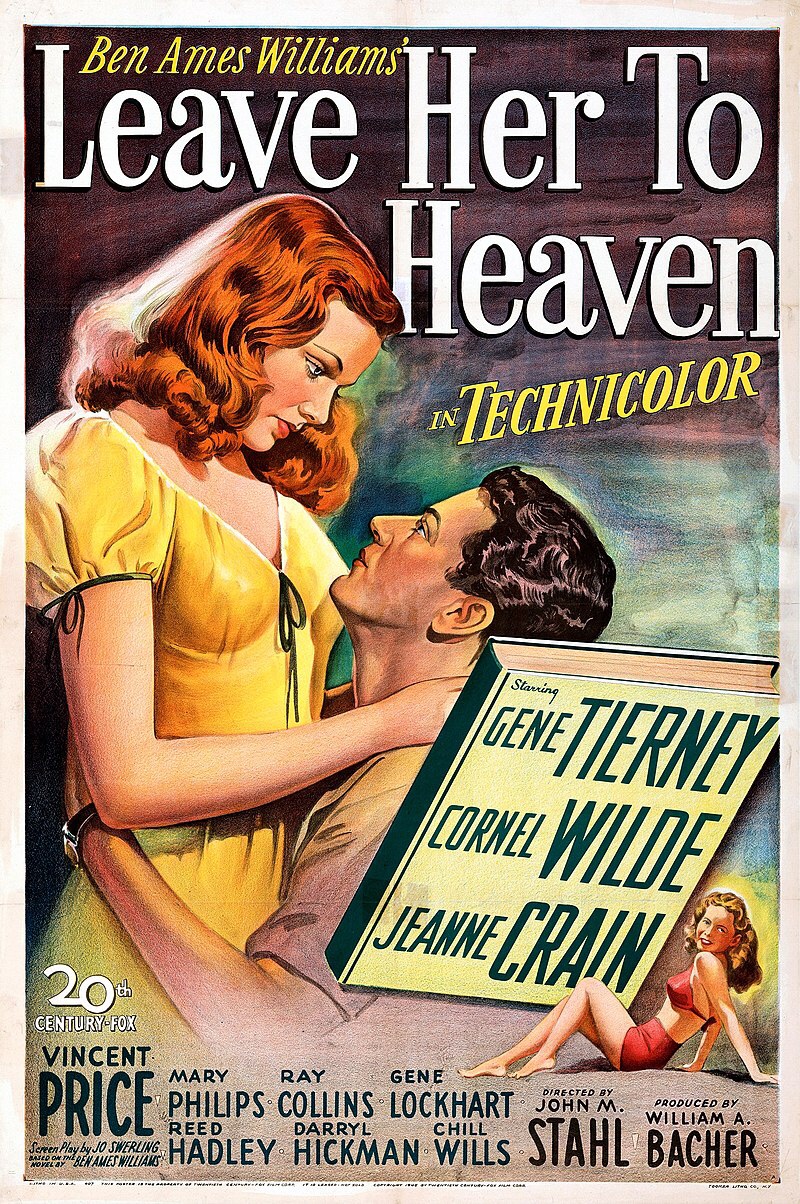

“There’s nothing wrong with Ellen. It’s just that she loves too much.”

Oh, there’s something wrong with Ellen, all right. Possibly the first and probably the best of the “psycho girlfriend” genre in cinema, made famous by Glenn Close’s and Michael Douglas’ sleazy Fatal Attraction (1987) – and Clint Eastwood’s directorial debut Play Misty for Me (1971) – this 1945 film is the eerie portrait of one of the evilest, most pathological women in fiction. It’s also available on YouTube for free (which I wish I’d known before renting it via a streaming service!).

Ellen Berent (Gene Tierney) is a beautiful socialite who seduces a novelist, Richard Marland (Cornel Wilde), purely because he looks like her late father. Her lack of interest in him as a discrete entity is signalled early on when, not knowing his identity, she admits to not liking his book very much.

She’s apologetic on finding out he wrote it, and when it happens that they’ll be sharing a ranch in Mexico, where she and her family have gone to scatter her father’s ashes, a whirlwind romance leads to marriage. But Ellen wants only him, and for him to only want her, living alone together at the Back of the Moon (their rural retreat) without interference from either his writing, her family, or his crippled little brother (Darryl Hickman)…

Leave Her to Heaven, its title taken from a line in Hamlet where the old king’s ghost tells the prince to not seek vengeance against the widowed queen, draws heavily on Greek mythology. Ellen’s characterisation is inspired by the Electra complex, based on the story of a woman who fell in love with her own father. Of course, from a Freudian perspective, most little girls go through a period of being “in love” with their fathers. Ellen just never grew out of that period. The dialogue I quoted at the start is from her mother, in response to Richard’s questioning. She may be reassuring herself as much as Richard.

Filmed in lush Technicolour, this earlier film improves on both Misty and Attraction. It’s more disturbing than either, despite its U for Universal (G for General Audiences in America) rating. Neither of the later films was all that interested in their antagonists as characters, presenting them more as force-of-nature psychobitches without histories or motivations, less grounded in a detailed arc than many slasher villains. (Close pushed for a more psychologically astute ending to Attraction that happens to somewhat reflect Heaven’s, though test screenings led to the visceral but absurd finale that we got.)

Tierney is magnificent as Ellen Berent. Unlike Alex Forrest (the Close character), you can see why someone would like and maybe fall in love with her. She’s beautiful, yes, a sexual icon of her era, but that’s not all she is. She’s also convincingly kind and normal to people who don’t know her well, and even to people who do. When her sister Ruth (Jeanne Crain) finally blows up at her, it’s only after two violent incidents, a lot of provocation, and probably a lifetime of making excuses for her sister. We don’t really like to believe the worst of each other, especially those we’ve known for so long.

One of the joys of movies like this is thinking about their themes and hidden meanings, below the protective surface that censorship demands. My suspicion is that Ellen was a victim of incest by her father, which her mother maybe to some degree suspected but didn’t have the language to address, and this is what lies behind Ellen’s pathology. A film from 1945 cannot address this directly either, leaving you to wonder why it is that Ellen became so obsessed…

Sidenote: A supporting role is played by Vincent Price before he entered his horror phase. Unless you count this as a horror film, which in a way I do.

Rating: 4/4

Leave a comment