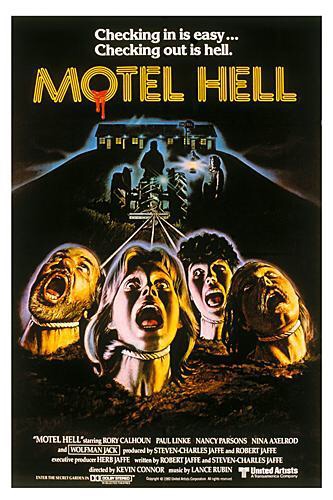

All the way back in 1980, over 15 years before Scream (1996), slasher films were still being parodied. Back then, movies like Motel Hell were referred to as “sleazoids” and “geek shows” by unimpressed critics including Roger Ebert, who nonetheless gave this film a rare-for-the-genre 3/4 for bringing laughter to the formula.

A sun-scorched and brilliantined, 58-year-old Rory Calhoun plays “Farmer” Vincent Smith, a motel operator who sells smoked meats with his sister, Ida (Nancy Parsons). Their slogan? “It takes all kinds of critters to make Farmer Vincent’s fritters.” You bet it does. The siblings have a sideline in using road traps to waylay motorists, at which point they drug them, sever their vocal cords, plant them up to their necks like cabbages in a secret allotment, and then eventually kill them for transport to the smokehouse.

In the meantime, local dim-witted sheriff Bruce Smith, who’s supposed to be Vincent’s younger brother but looks more like his son (given the 26-year age difference between the two actors), romances their new guest. She’s called Terry (Nina Axelrod) yet is definitely a girl, and her boyfriend Bob is currently a head of cabbage in the farmer’s field. Having “rescued” her from the crash that he caused, Vincent and Ida appoint themselves as her caregivers until she recovers, though Terry and eventually Bruce become suspicious of what’s going on in the smokehouse…

Motel Hell occupies an unusual liminal space between styles and genres, not quite a parody in the vein of Airplane! (1980) but also not a straight-faced horror sleazoid like Mother’s Day (1980). (1980 was a good year for silliness and sleaze…) The sleazoid films that were later codified into the slasher genre are generally light on plot and character, assuming a raft of Freudian psychobabble to justify the violence and then building their narratives around their splatter-y set pieces. They (probably unconsciously) tended towards the misogynistic in their “woman in peril” contrivances.

(Suspense director Brian De Palma justified the “woman in peril” trope with the observation that “Women are more sympathetic creatures in jeopardy, plus they’re more interesting to photograph. I’d rather photograph a woman walking around with a candelabra than a guy.” Meanwhile, the academic Carol J Clover spun a whole book out of analysing the sociopsychological factors underpinning this, 1992’s Men, Women, and Chainsaws: Gender in the Modern Horror Film.)

Motel Hell rises above its peers’ limitations, producing a bizarre but engaging plot with simple yet distinctive characters, eschewing the misogynistic fascination with sexual serial killings (while also fitting in a lot more boobage than the so-called sleazoids often had, from then-25-year-old Nina Axelrod). The film was initially intended to be just another entry in the subgenre, and you can see how that would have played, Farmer Vincent targeting a group of teenagers until a final girl emerges from them. It was tilted towards humour due to budgetary constraints, and against all odds became a really quite impressive, even classic, B-movie.

It’s even oddly believable, human cabbages aside. There’s a pretty wonderful scene where Vincent, Ida, Terry, and Bruce are picnicking together when the siblings share a story about when Vicent slaughtered and served their grandmother’s dog for dinner. It’s amusing, however, it’s also genuinely uncomfortable. Terry is our surrogate here, recoiling in discomfort, while Bruce is the medium. The story doesn’t seem that strange to him, since he doesn’t understand that his siblings have moved on from household dogs to even more socially unacceptable meats. In its own weird and satirical way, Motel Hell has as much to say about madness in backwoods America as The Texas Chain Saw Massacre (1974).

Anyone who reads true crime will know that even some of the story’s silliest turns, like when Terry becomes enamoured of Farmer Vincent (giving Calhoun a chance to grab some knocker more than half his age), aren’t outside the realms of possibility.

Motel Hell is still definitely a B-movie, with all the pacing and production issues that the type can entail. It also lacks a relatable protagonist in Sheriff Bruce. (This might just be an ’80s thing that I should get past, but I struggled to find the guy a useful protagonist following a scene where he puts his hands all over Terry while she’s telling him no.) It rises above its limitations with intelligent writing and directing, though, and a sense of humour both silly and black as tar. It’s genuinely eerie and perverse in its “farming” scenes, and it stands out as good entertainment in its sleazy milieu.

Rating: 3/4

Leave a comment