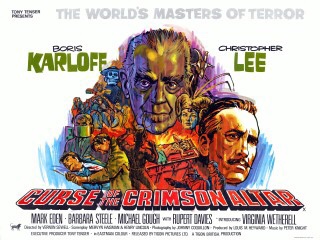

It’s possible to interpret Curse of the Crimson Altar, on the surface another hoary old tale of black magic and fleeting nudity in the same vein as The Devil Rides Out (also ‘68) and The Skull (1965), as a transitional sort of swan song in British horror. It’s very much an old man’s film, the penultimate by director Vernon Sewell (although he’d live for another 33 years, passing at a wizened 97 in 2001) and Boris Karloff’s last appearance before dying a year later; after this, he made a quartet of Mexican horror features that were released posthumously.

Amazingly, Christopher Lee was only about 46 when he starred here. He’s one of those actors who always looks to be somewhere in his mid-50s or older just because he has such a patriarchal presence and gravitas, which is partly why he works so well in horror films. When a man like that tells you that up is down, east is west, and he’s definitely not sacrificing virgins to Baphomet in the garden, a part of you wants to believe him even as he’s holding a bloodstained dagger and wearing a schoolgirl outfit.

I was surprised on researching Crimson Altar, which I saw at my local art centre’s Classic Horror Nights, that it’s based (uncredited) on one of my favourite HP Lovecraft stories, “The Dreams in the Witch House”. I certainly didn’t see the connection while watching. The thing about Lovecraft is that there’s always a sci-fi or “cosmic” element, it’s never “just” witches and so forth, so in that story, the witch Keziah Mason has a familiar and all the rest of it, but what she gains access to is an alien world of beings whose intelligence is developed to a psychic point far beyond our own.

Crimson Altar (known as The Crimson Cult in America) reminded me more of “God Grante That She Lye Stille” by Lady Cynthia Asquith, about a long-dead English witch haunting her ancestral pile. The film’s plot is that Robert Manning (Mark Eden), an antique dealer (an oddly popular job for British horror film protagonists), visits Craxted Lodge in the village of Greymarsh to search for his brother and colleague.

Michael Gough – best known internationally for his work as Alfred Pennyworth in Tim Burton’s and Joel Schumacher’s Batman films – appears in the prologue as a farmer lured by Lavinia Morley (Barbara Steele), a blue-skinned witch who makes him sign his name in the Devil’s book. Thereafter, Manning meets at Craxted Lavinia’s ancestors, lord of the manor Morley (Christopher Lee) and his niece Eve (Virginia Wetherell), as well as Professor John Marsh (Boris Karloff), a wheelchair-bound expert in the occult. One or more of whom may know more about Manning’s brother’s fate than they’re letting on…

The film is structured a bit like a murder mystery. Manning gets a bit more characterisation than protagonists of this type and era often do. Not much, but he has a convincing normalcy and scepticism about him. I liked that he reports what strange things happen to him for a long time straight to Morley, not realising that the latter might have sinister intent. In another film, this might have made Manning seem gullible, but here it works. Morley’s the lord of the manor and seems like a decent chap, after all; plus witches aren’t real, surely?

The pace is a little slack and you’re left wondering if there’s a weirder and more intriguing film inside this more conventional one based on some of the directorial flourishes. For instance, there are kaleidoscopic shots meant to evoke a bleed between our and the spirit world and which feel like they belong in a David Lynch film, almost.

Lee and Karloff provide a lot of entertainment value and are the real onscreen heavyweights here. Eden and Wetherell are compelling and convincing protagonists, but Lee and Karloff anchor the film. Right at the end of his life here and with only half a working lung, Karloff rarely leaves his wheelchair and when he does you worry that he’ll topple over. He exudes charisma, though, and watching him is like spending time with the granddad that you wish you had. Lee does his usual thing, lending authority and nuance to a character that isn’t all that well-developed in itself.

Some aspects of the story have aged unfortunately. Although both Eden and Wetherell are likeable, his “seduction” of her is very much of its time and liable to make a postfeminist, let alone post-Me Too audience squirm. At one point he all but pounces on her from her own bed.

Still, although it’s not a masterpiece it’s a good bit of fun if you like this sort of thing, and a must-watch for Karloff completists of course.

Leave a comment