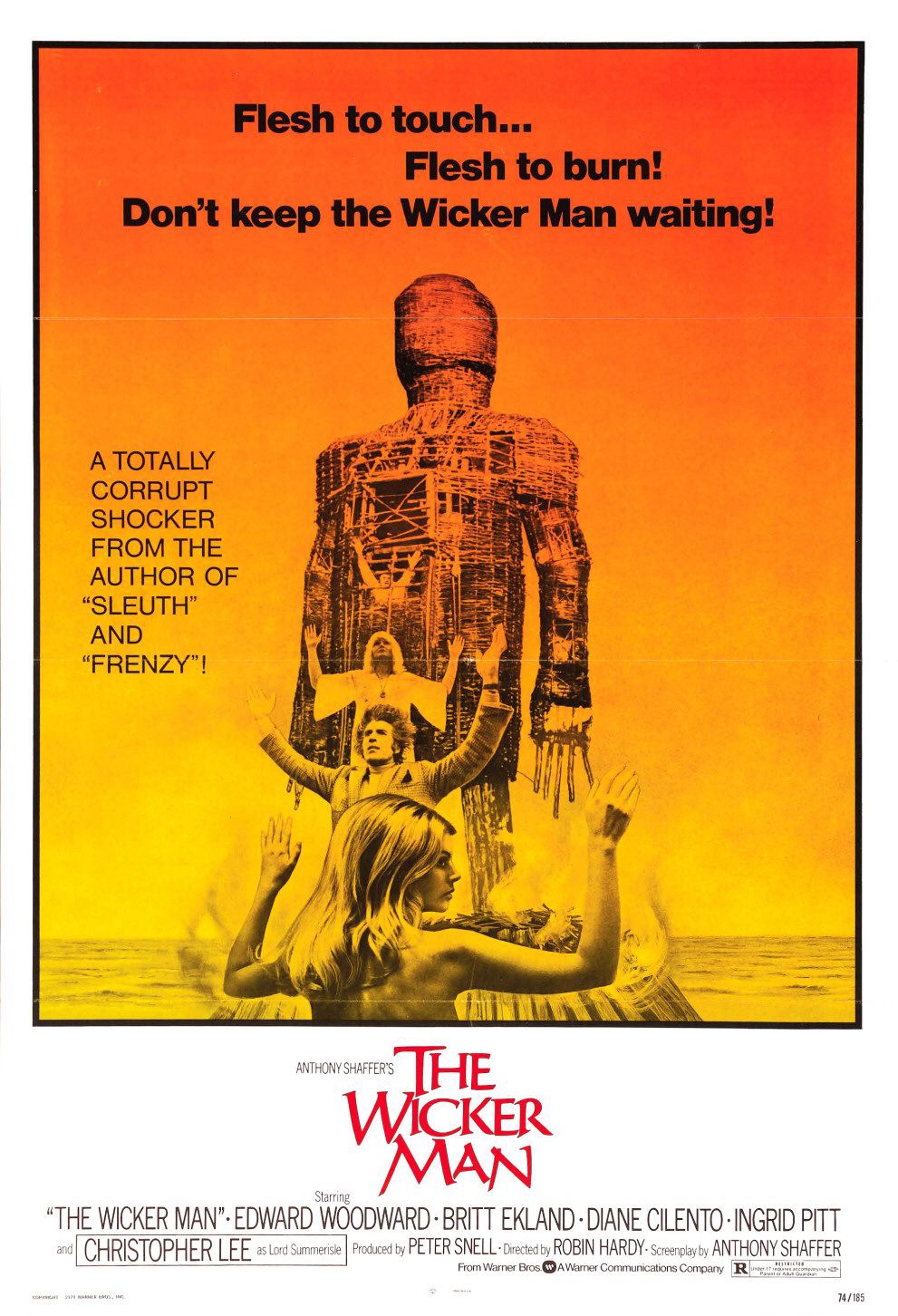

I just saw a restored edition of 1973’s The Wicker Man in the cinema for its 50th anniversary and it was a heartwarming tale of faith against adversity.

Well, maybe not. But it was a good detective story that develops into a tale of horror and madness as old superstitions come up against modernity. The plot is that Sergeant Howie (Edward Woodward) is a puritanical Christian Scot who comes to Summerisle, an island off the coast, to investigate a child’s disappearance. But he soon finds that under the leadership of Lord Summerisle (Christopher Lee), ancient pagan beliefs are observed, potentially including human sacrifice…

“Evil pagans” are a stalwart of British horror fiction. These days it’s probably an un-PC one, and rightly so since most pagans who observe their faith are perfectly nice men and women, more inclined to post TikToks of themselves dancing in stone circles than kidnap virgins and hang gizzards on trees. The sub-genre goes back to ghost stories by writers like MR James and EF Benson, for example, “The Man Who Went Too Far”, Benson’s short story about a silly fellow who decides to worship the Great God Pan and ends up trampled by a goat.

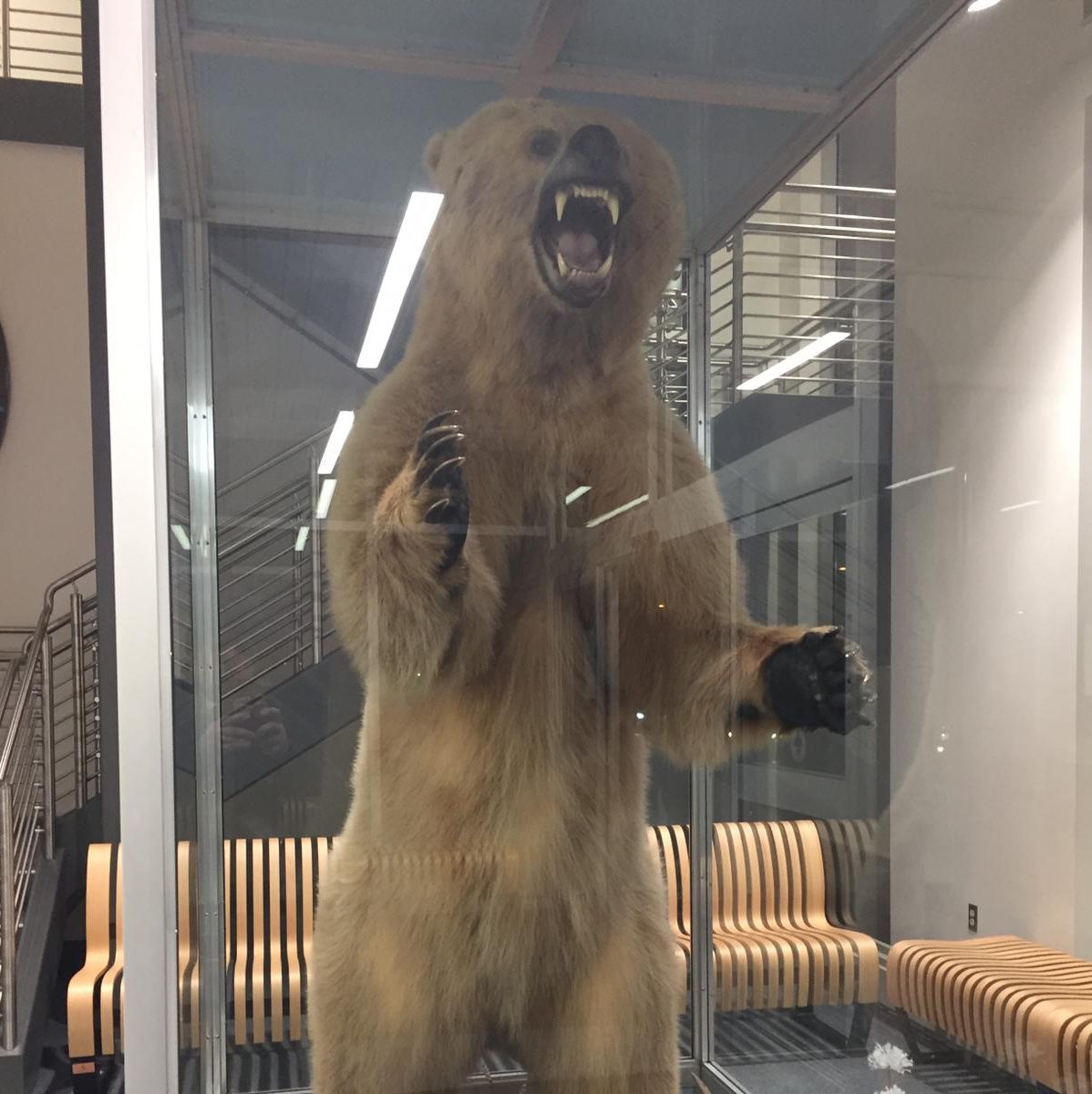

The Wicker Man is arguably the last hurrah of this genre, the final serious outing before it resorted to either abstract symbolism or self-aware humour. Neil LaBute infamously tried to remake it for Americans in 2006, the film of the same name starring Nicolas Cage and focusing on action violence that was no doubt meant to modernise it but ended up launching a thousand memes. (“Not the bees!”)

What LaBute’s version failed to understand was that what happens in the story isn’t so much the point as why it does. It’s not that a sacrifice is made, it’s that it’s made for no good reason, just insane superstition.

By 2006 the pagan angle was no longer enough and instead, LaBute had to make Summerisle a matriarchal community, supplanting the fear of heresy with the fear of female rule. Ironically, it’s more dated now than the ‘73 original, which has its moments of awkward seventies filmmaking, but at its core retains a feeling of timeless horror. This is absent from LaBute’s effort, a dimwitted cheese-fest that’s very much of its time, a point in the ‘00s that was post-slasher but before our current renaissance.

Robin Hardy’s original isn’t perfect. There’s a scene early on that wasn’t restored for the edition I saw, retaining its grainy TV-level quality, wherein Lee introduces a young suitor to the embodiment of Aphrodite and then expounds the movie’s theme. It’s a drawn-out and needlessly explanatory scene that slackens the tension and reduces the effectiveness of Lee’s introduction later on, which should be the first time we see him.

Elsewhere, Sgt Howie explains aloud what he discovers when he doesn’t need to as if Hardy doesn’t trust his audience to interpret visual information. The music choice for a chase scene is also very dated, seeming more appropriate for a traditional action film than horror.

However, the story’s ghoulish effectiveness remains. I’d forgotten how central music is to why the film works. Its folksy soundtrack doesn’t just complement but also structures the plot, guiding us from scene to scene, beginning with gentle and reverent tunes before introducing bawdier songs about the landlord’s daughter, chants around a bonfire at Lord Summerisle’s manor, and so on. The musical scenes have abundant energy and create a sense of a community bound together as one by their traditions.

Lee is excellent, as ever. Only an actor who exudes intelligence and authority as he does could have made Lord Summerisle such a fascinating character. He’s lordly and good-humoured, supportive of his subjects, a justice of the peace who represents the ideal of what such a figure should be. That he’s also insane only adds to his authority, since he shares the insanity of his people.

Woodward, meanwhile, is a perfect counterpoint. Repressed, and authoritarian himself, but in a much more conservative sense. He could easily have seemed too sanctimonious, though even at his most dogmatic he symbolises reason.

What I find remarkable is that, despite the occasional giggle (such as when a teacher lectures schoolgirls on phallic symbolism), the film doesn’t lapse into unintentional humour. Even when Lee drags up to play a multi-gendered figure from pagan mythology, he doesn’t seem silly but rather lit with the mad light of what he thinks is justified true belief.

For me, The Wicker Man isn’t really about pagans versus Christians, that’s just its surface theme. It’s really about the futility of all superstition, and how such pseudo-scientific madness can persist in the modern age. A Summerisle mother “cures” her child’s sore throat by placing a frog in her mouth. To this day, a frightening amount of people believe that vaccines cause autism and that COVID is a hoax.

Sacrifice won’t make your apples grow again, Sgt Howie pleads. But it’s no use. These people have built their identities around their beliefs, and they’d rather descend into violence than accept that what they’ve built their very selves on is wrong. Sound familiar?

Leave a comment